The key points to finding great companies are threefold:

-

Non-quantitative indicators: Management, corporate culture, and reputation;

-

Quantitative indicators: Financial statements;

-

Core metrics: The ability to create value, measured by ROIC and ROE.

-

Evaluating non-quantitative indicators requires long-term tracking of a company. Frequent on-site research helps understand corporate culture, management teams, and their capabilities through prolonged observation of operations.

-

Assessing quantitative financial metrics demands solid financial knowledge. Reading financial statements goes beyond simple revenue and profit figures - it requires deep analysis to determine operational quality, identify potential fraud, and assess growth potential.

-

The core of evaluating a great company lies in judging its value creation ability, measured by ROE (Return on Equity) and ROIC (Return on Invested Capital).

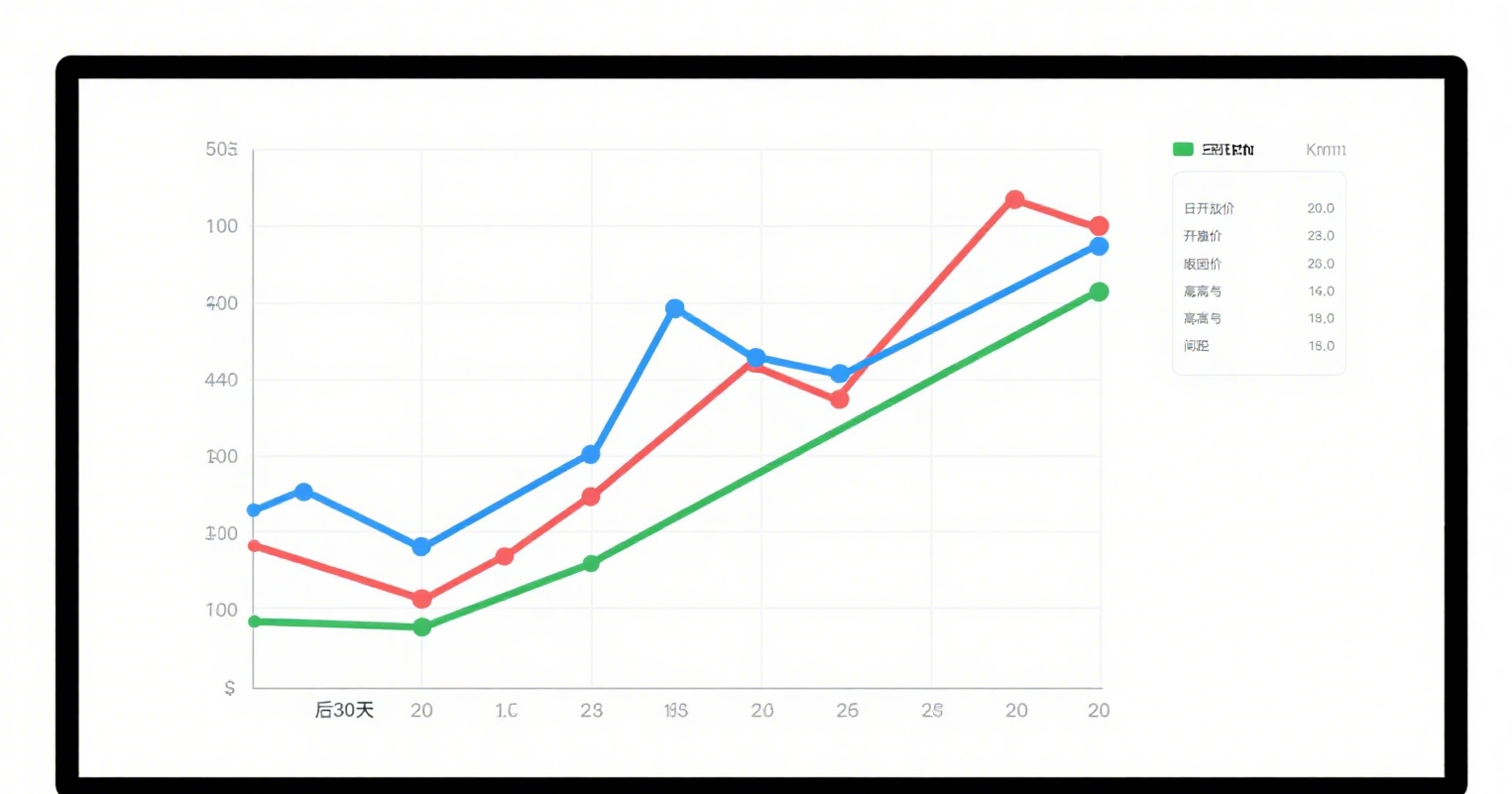

Why these two metrics? Because simple valuation methods like EPS or PEG can be misleading. For example: Company A earned 10,000 last year and 100,000 this year (10x growth); Company B earned 100 million last year and 200 million this year (2x growth). In reality, everyone knows Company B is better, but capital markets often focus only on growth rates (especially in China). ROIC and ROE directly reflect a company's input-output efficiency, showing whether it creates or destroys value, its competitive advantages, whether performance is sustainable, and the quality of growth.

From an ROIC perspective, most stocks in China's market are destroying value. Many companies maintain ROIC below 6% long-term, unable to beat basic interest rates, let alone inflation. Even if profits multiply suddenly, it's meaningless for these companies with low profit bases. Some don't generate real profits at all - their apparent wealth exists only on paper, relying on continuous fundraising or excessive financial leverage, where high returns correspond to high operational risks.

If a company consistently destroys value, no price is cheap enough to buy. Therefore, truly great companies - whether growth or value stocks - share these traits: high output with low input, excellent management (avoiding high ROIC but low ROE situations), and sustainable operations as their ultimate goal.

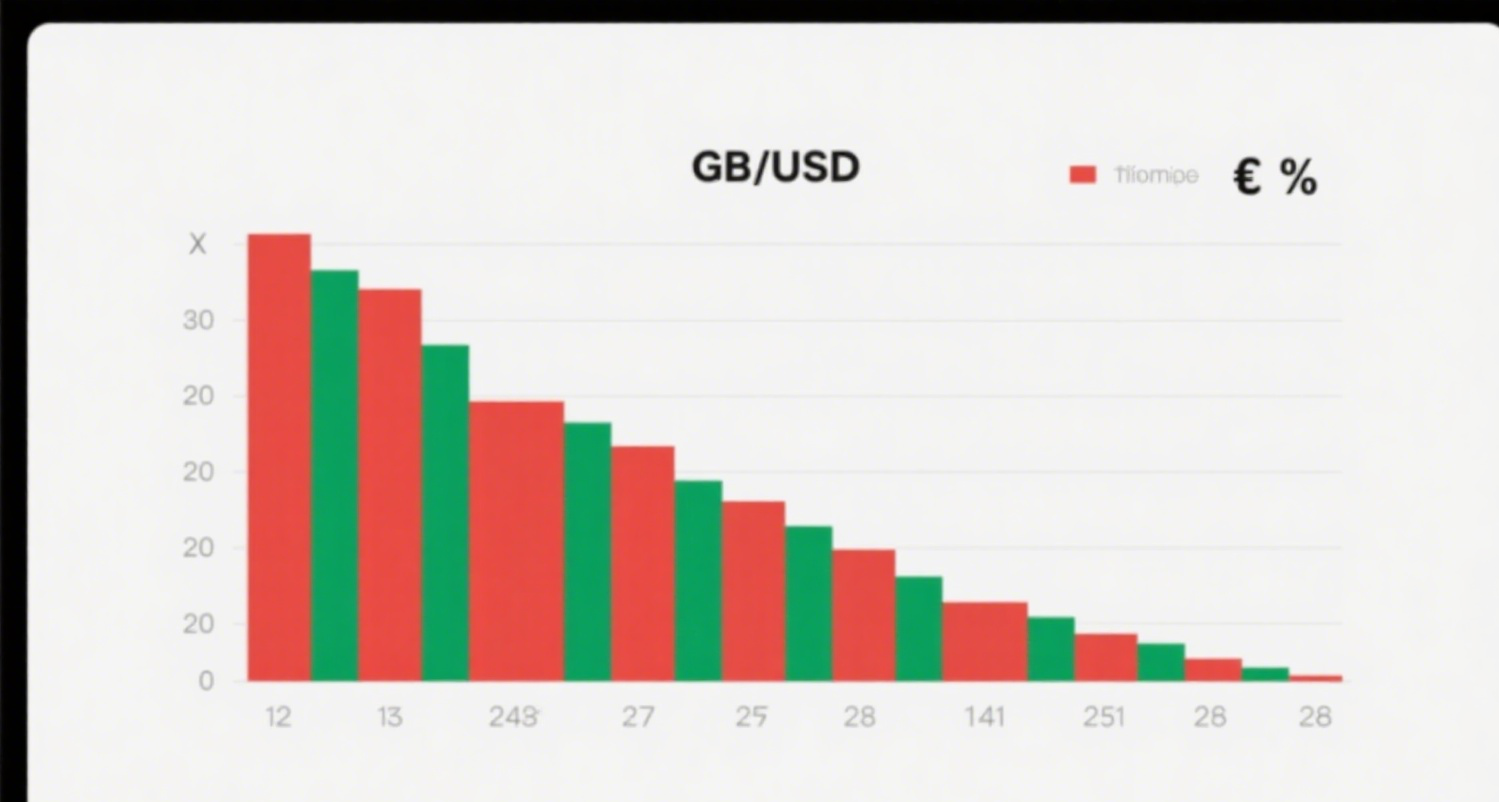

Finding good prices requires deep understanding and analytical ability regarding human nature, markets, and capital.

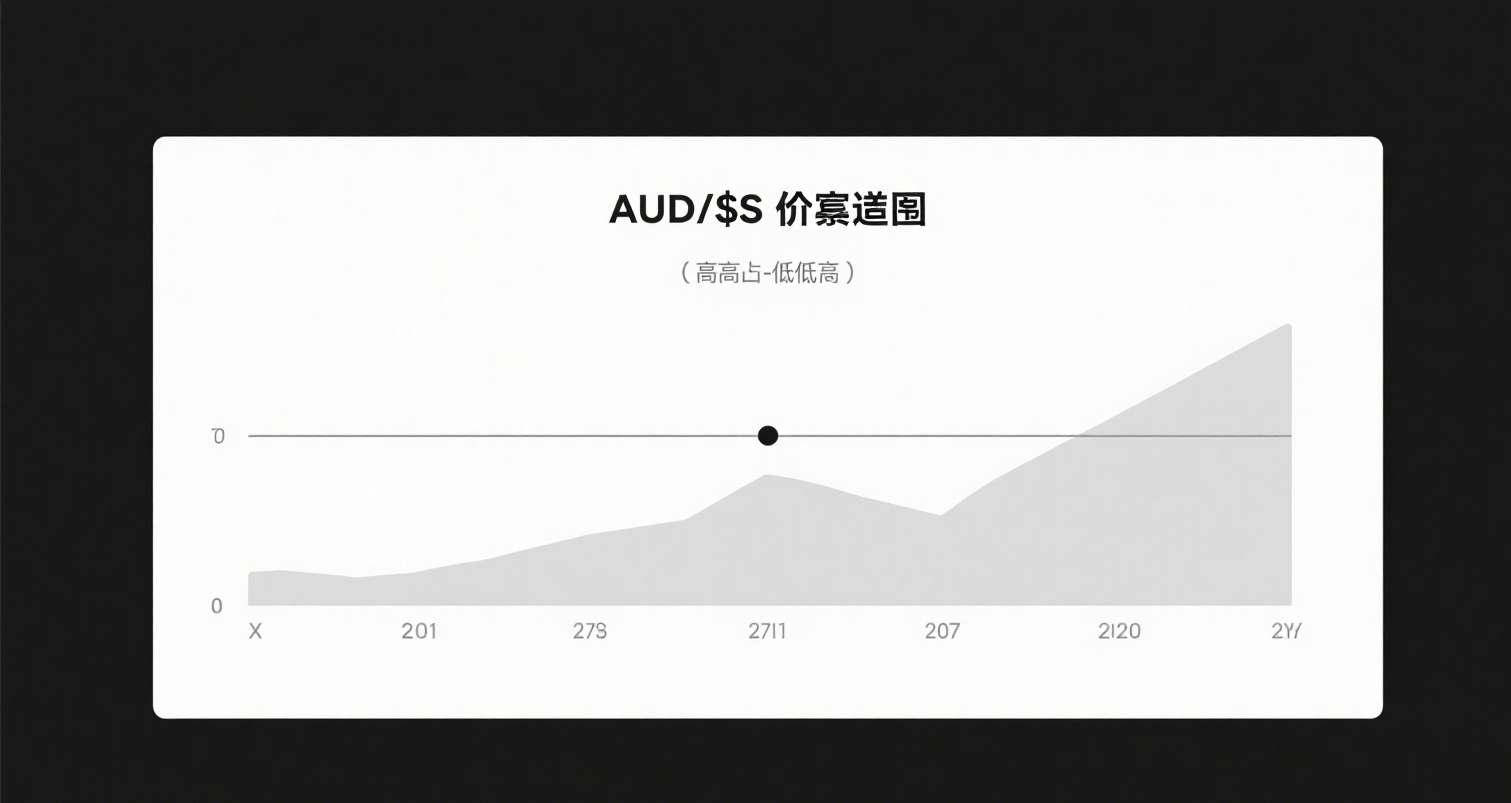

Many investors mistakenly believe valuation models should determine buying prices after finding good companies - this is fundamentally wrong. Valuation models determine long-term safety margins (technical analysis is even more absurd as indicators merely summarize history), while current prices depend on analyzing human nature and market behavior.

This makes sense because markets are efficient long-term (hence valuation models for safety margins), but trades happen now when markets are often inefficient short-term. Short-term price movements reflect human emotion and capital flows rather than fundamentals. Even precise "safety margins" calculated through models may prove worthless due to market inefficiency (though valuation systems remain important despite potential collapse in extremes. Note: ROE/ROIC evaluate company quality, not price levels). As masters advise: "Investing is an art, not an exact science. Better roughly right than precisely wrong."

This explains why most investors, no matter how hard they study or how much experience they gain, can only become good investors - becoming truly great is nearly impossible. The world's great investors are rare because their price-value discovery ability isn't acquired through learning; spotting good prices is nearly innate, and their understanding of human nature and markets cannot be replicated.